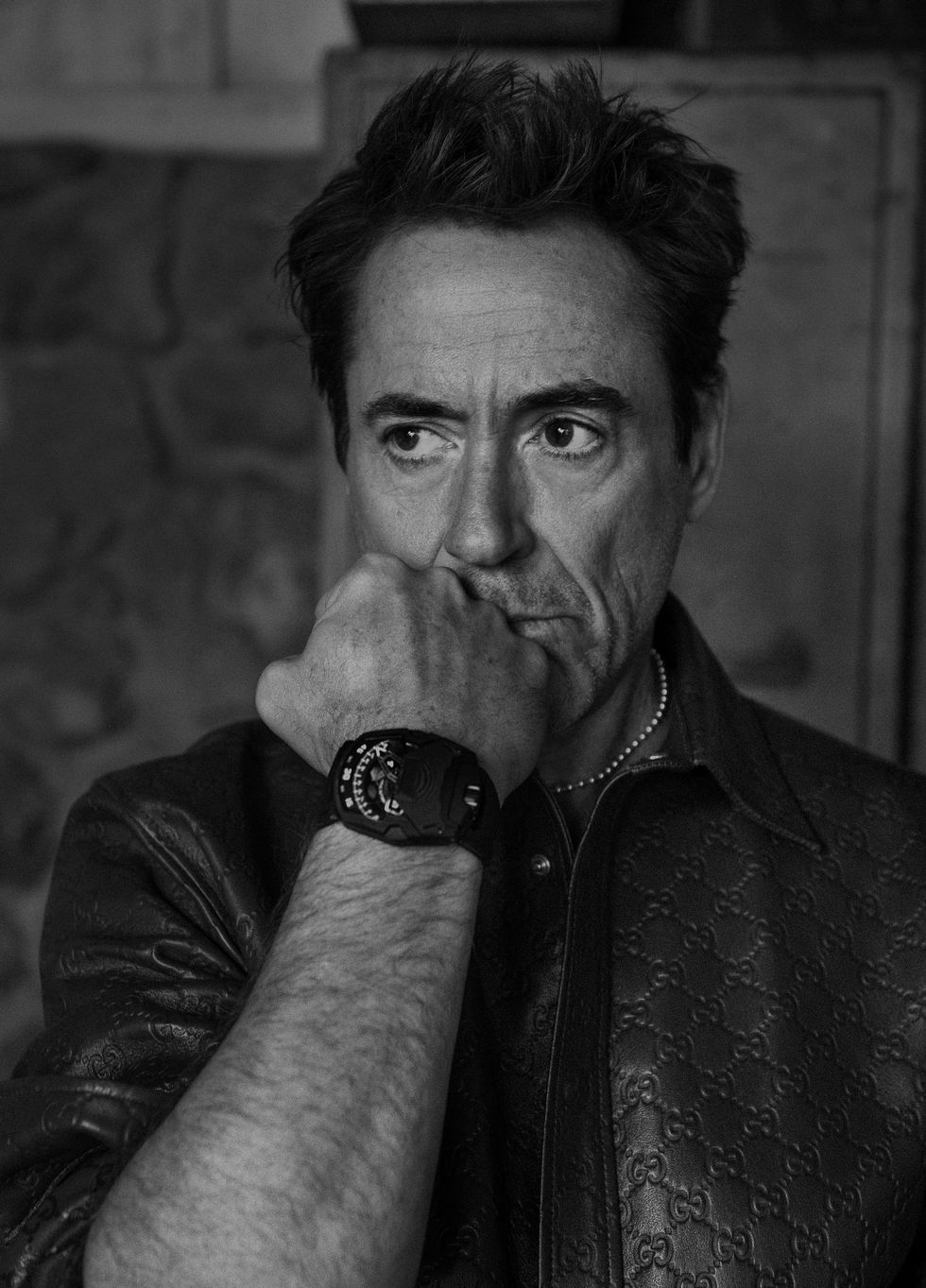

Where were Winnifred and Willow? Last night he came downstairs around bedtime and didn’t see either of them. This alarmed him. He wasn’t worried about Monty—Monty’s an old cat, shows up when he pleases. But the two rescue kittens aren’t as worldly as Monty is, and there are hawks here in Malibu, which is why last year Robert Downey Jr. hired the host of the television show My Cat from Hell to come and rig up all kinds of gates, tents, fences, and special cat doors, everything wrapped in camouflage netting—what Downey calls Catification Zones. Because Downey knows that if he lets anything happen to the cats, Susan and the kids will vote him out on the street.

It had been a normal Friday evening, full of the smallness of life that sustains Downey these days. His son Exton plays in the sixth-seventh-eighth-grade basketball league and they’d all gone to his game at the high school, after which Exton went to a sleepover. The house was quiet now—the chef had gone home; the alpacas (Dandy, Fuzzy, Sadie, Jess, and Buttercup), the goats (Cutieboots, Memo, Zoltar, and Pepper—the only one Downey’s kids let him name), and the other animals were asleep outside; and Downey was maybe going to find something new to watch on his iPad Pro now that he’d finished The Curse.

But where were Winnie and Willow? He called to his nine-year-old daughter, Avri, in her room, and it turned out that the kittens had crawled up inside her bed frame, either trapped or hiding, and she couldn’t lure them out. There’s no bottom under the frame—it’s like a futon—plus Avri has about a hundred blankets on her bed (“like chain mail,” Downey says), so they were both peeling off the covers while he was trying to lift the mattress and reach under and then blam! one of the cats came flying out, scared the crap out of him, and the other one went that way and—

It was a whole thing.

He’s telling me this over a cup of coffee the next morning. Why is he telling me this? I don’t know, but it’s funny. I then knock over my coffee—this is one minute into our interview—and look frantically for something with which to wipe the umber splotch off his white kitchen table. But he says, “No, don’t touch it!” He splays his hands in the air, staring at the spill as if he were framing a shot. “It’s perfect.”

I look at the spill and—well, it is . . . kind of . . . perfect.

By pretending that my klutz move was an act of inadvertent artistic creation, Downey has, in this moment, saved me from humiliation. I didn’t know it then, but it was clear when I listened to the tape later that from that moment on, for the next five hours, this interview would be different. He would lead, and I would follow, and it would hardly clock as an interview at all but rather a sort of conversation. In fact, it would be unlike any conversation I had ever had in my life.