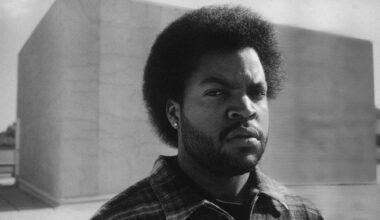

“For a long while I would only ever take the back streets. I didn’t want to walk on the Boulevard and deal with a cop’s attitude,” recalls Ice Cube of the years that directly followed the release of anti-cop anthem “Fuck Tha Police”. In this still controversial 1988 song by his pioneering group, Ni***z Wit Attitudes (or N.W.A), the emcee half-grunted the immortal words: “[I’m] not the other colour so police think: they have the authority to kill a minority.”

Cube – real name O’Shea Jackson Sr – continues: “The police in Los Angeles will kill you; they will set you up and murder you right there on the spot. After ‘Fuck Tha Police’ dropped we felt like we had to be extra cautious in how we moved. I remember Ice-T told me: ‘Don’t let the LAPD catch you in a twist!’” Did he need eyes in the back of his head, then? “Definitely. Remember: America has an avenue for guys like us! You either get a 9-to-5 and work for someone or they have a jail cell for you. They also have the cemetery for you, too.”

The CEO and businessman behind a fast-rising 3-v-3 basketball franchise (The Big 3); a mainstream political pundit who regularly appears on everything from Fox News to CNN; and the voice actor behind the villainous Superfly in this year’s hit animated movie Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Turtle Mayhem, it’s fair to say the 54-year-old Ice Cube is in a much more comfortable space than the hungry teenage emcee who – alongside NWA’ soldiers Eazy-E, Dr. Dre, MC Ren, and DJ Yella – threw lyrical grenades at pompous authority figures. Yet this candid anecdote serves as a powerful reminder of the anti-establishment blues that propelled this rap legend from South Central, Los Angeles into pop culture folklore, and how eviscerating crooked LAPD officers on wax left such a big target on Ice Cube’s back.

Chuck D famously remarked that “rap music was CNN for the ghetto” and Cube is more than happy to indulge in my theory that N.W.A. were sometimes more like journalists than emcees, particularly when it came to shining a light on America’s crack epidemic and the rise of inner-city gangs. “I was there when it went from a safe type of neighbourhood to all of our role models suddenly getting hooked on crack,” Cube recalls. “It was devastating to see. I didn’t feel like it was my responsibility just to rhyme and was more to show people what was really going on in the hood. Gangsta rap was the phrase they coined [to describe me], but I saw what I did on a song like “Dope Man” as sharing street knowledge.”

These days Cube’s name is rarely in the headlines for actual music, with divisive political moves – including working with the former Trump administration and turning down a $9m movie role because it required him to have the COVID-19 vaccine – inspiring endless (and highly critical) think pieces. His management pre-warns me that the rap legend won’t consider talking about the current US government or any of his past controversial political comments.

Cube has also starred in family-friendly road trip movies (see ‘Are We There Yet?’); re-defined the Black comedy in Hollywood via 1995’s Friday; teamed up with J-Lo to take down an evil anaconda snake; and pulled a baby dinosaur out of a magician’s hat alongside a shocked Elmo (yes, really) during a cameo on Sesame Street. In other words, he’s long transcended the ‘gangsta rapper’ tag.

However, beyond this diverse portfolio, you sense it is all of Cube’s astonishingly prescient raps from hip hop culture’s golden era that remain the beating heart of his legacy. After birthing gangsta rap as we know it with N.W.A, Cube boldly left the group at the start of the 90s to embark on an explosive solo career. He briefly moved from the West to the East, infusing his instinctive P-funk leanings (FYI: Parliament’s George Clinton was a childhood hero, and collaborator, who Cube once queued for “hours and hours” to meet for an autograph at a LA record shop) with blunter boom bap textures and more of a militant edge, courtesy of Long Island-based producers The Bomb Squad.

On subsequent classic, 1990’ solo debut Amerikkka’s Most Wanted, Cube rapped with the energy of a vengeful rottweiler that had chewed through its leash and gone on a rampage in the president’s war room. He questioned why there were more Black people in prisons than in American colleges [“The N***a You Love To Hate”] and even ingeniously flipped nursery rhymes into bleak cautionary tales [on “A Gangsta’s Fairytale” Lil Bo Peep was a “smoked out” junkie], ultimately highlighting how kids in America’s inner cities were robbed of both their parents and childhood innocence. The record that followed, 1991’s Death Certificate, was even better. The artwork depicted Cube – doing his trademark piercing, mean mug stare – stood next to the corpse of Uncle Sam. The imagery seemed to suggest The American Dream was lies and simply propaganda that the people in his neighborhood should violently resist.

In an LA that had been rocked by the vicious and unlawful beating of Rodney King by LAPD officers, this 1991 sophomore record was the soundtrack for the resistance: particularly the pulsing, if slightly demented jazz loop at the core of “Horny Lil Devil” and the promise to turn a KKK member’s “white sheet into a red cloth”. On ‘Alive On Arrival’ Cube broke down how American hospitals deliberately left Black people to bleed out and die “on a nasty ass carpet”, and with “Who Got The Camera” he spoke about the need to film police brutality decades before George Floyd was choked to death in the street. Talking about the latter song, Cube says: “I always knew no matter what misdeeds you captured on film, there’s certain people in society who have the power to make it all go away.”

With Death Certificate Cube tended to rap with a snarling vocal: the rap music equivalent of the brutal truths barked out by R. Lee Ermey’s infinitely quotable drill sergeant to terrified military simpletons in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Any politically minded rapper that followed – from 2Pac to Killer Mike and billy woods – was an obvious extension of Ice Cube’s prophetic messages.

Arguably, Cube’s most iconic solo song remains 1992’s “It Was A Good Day”, with this melancholic yet buttery smooth Isley Brothers-sampling banger essentially the hip hop equivalent of Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day”. Reflecting on this gem off 1992’s The Predator album today (which has nearly 1 billion streams on Spotify), Cube explains: “When I was dodging the stuff I was trying to escape, it was terrible if it happened to you. If I could [successfully] navigate through a day with the police looking for me, cowards on the corner waiting to shoot me, and people wanting to jack my car, then that was a good day. It meant that I did something right.”

Yet critics argue that the Cube who sold 10 million records globally by sharing ugly truths, telling yuppies to “bow down”, and rallying against republicans (on 2018’s “Arrest The President” it was Donald Trump who was in his crosshairs), has backtracked on a lot of these core values. In October 2020, Cube suffered a backlash after announcing a collaboration with the Trump administration on what was called a Platinum Plan for Black America.

He claimed the move didn’t reflect his political allegiances and was more about starting an open dialogue to create meaningful change, complaining in one tweet: “‘I get the president of the United State to put over half a trillion dollars of capital in the Black Community (without an endorsement) and N****s are mad at me?” At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, he also shared conspiracy theory memes that were widely condemned as antisemitic, although he later insisted they were “pro-Black” when defending himself against fiery criticism.

Cube believes there’s currently a vacuum of politically minded emcees in mainstream rap and artists willing to say – rightly or wrongly – what they feel in their lyrics, regardless of the consequences or public fallout. “Political rap isn’t rewarded by the music industry anymore. Now the youngsters just want fame and fortune. Only certain rap artists want to speak for the people,” Cube claims. “These records are like time capsules and they’re going to be around longer than you: so, if you have a microphone you better use it for good and not just potter your life away!”

Are there any current rappers he is inspired by? “I think J Cole and Kendrick Lamar are both great artists with something to say. Otherwise, everyone sounds the same. There’s too many auto tune effects, so the rap voices aren’t distinctive like they used to be.”

Reflecting on his origins, Cube reveals to me the first rhyme he ever wrote – “My name is Ice Cube, I want you to know / that I am not Run DMC or Kurtis Blow” – and how it spoke to a Californian kid tired of New York’s stranglehold over hip hop. All these years later, he believes this year’s Hip Hop 50 celebrations were far too biased towards the East; an obvious example of history repeating itself. “The West Coast has always had to bark real loud to be heard. When hip hop hits the 75-year-mark, they better give more love for what the West Coast did for this.”

While I have Cube in such a reflective mood, I’m keen to ask him whether he regrets any of his previous lyrics. Jay-Z has expressed regret for calling women “bitches” on his hit song “Big Pimpin”, and I wonder if Cube feels the same way.

“Some lyrics I wish I could have rephrased or I wish people could really understand exactly what I meant with this phrase or that phrase,” he replies, “but would you go back and change a masterpiece because of one lyric? No, don’t touch it!” He says it’s pointless judging historical art by today’s very different social values. “It is really about people’s feelings now. If they like you, they will give you an excuse for your lyrics. If they don’t? They will hold you accountable for things you said at 20, which is crazy. It is very shallow.”

Looking ahead to the future, Cube says he’s encouraged that women now dominate the rap landscape as well the feeling ageism is becoming less and less of a thing in today’s climate. “All young people want to be old one day. That’s the dream career. If the Rolling Stones can get up there and still do it at 80, then why can’t rappers?”

I tell him I’d like to see N.W.A re-form and give us their perspective as more philosophical veterans. “I am always down for something like that!” he answers. “It is really on Dr. Dre, though! If N.W.A gets back together then he would have to produce the music and be inspired to do it.” However, one thing he wouldn’t want is for the late Eazy-E to be resurrected or re-created through artificial intelligence technology.

“I don’t want to hear an AI Elvis or Bob Marley either,” he clarifies. “Take acting. When you love an actor, what you really love is their choices: why did he scream that line or whisper the other one? AI takes the essence away; it isn’t their choice anymore. AI re-creations of dead artists are being puppeteered by an executive. Who wants that shit?”

As our conversation winds down, I quote a lyric from “When I Get To Heaven”, an underrated Ice Cube’ deep cut where the artist spits: “Heaven isn’t just wealth”. So, what does heaven look like for Ice Cube in 2023? He concludes: “Everybody being healthy and no one in the hospital. You can be the richest man in the world, but if you are unhealthy, your money means nothing! As long as I am healthy and continue to be inspired, I should be able to be here [rapping] forever.” You can expect the “street knowledge” to keep coming for a long time yet.