Shea Jackson wasn’t always destined to be Ice Cube. As a teenager, he’d flipped between ambitions of drawing buildings and writing rap lyrics, before eventually studying architectural drafting at the Phoenix Institute of Technology in Arizona. In the summer of 1987, he was loading his car in South Central Los Angeles, prepping for the 400-mile drive out to Phoenix, when Dr Dre, then a budding producer with the World Class Wreckin’ Cru, rolled up with a box of records that looked something like the future.

“He had our first single from NWA, which was ‘Dope Man’, with ‘8 Ball’ on the other side,” remembers Cube today. “He pulled up with the cover” – there’s Cube, Eazy-E, Dr Dre, MC Ren, and a posse of others dressed in jeans, baggy tees, and baseball caps, all backed into an alleyway splattered with graffiti tags. Goofy, Flavor Flav-aping clock necklaces swing from a few of the crew’s necks; the ground is strewn with spent bottles of malt liquor. “This is my first time seeing the actual record. And Dre was like, ‘Are you sure you want to go to school? Because this s*** about to pop.’”

Cube chose to stick with his studies, but watched on keenly as Dre’s prediction came good. By 1988, Cube had his diploma, and NWA were on a run of hit records. Cube’s pen was responsible for both. Within a year, the group would be recognised – and demonised – as the pioneers of gangsta rap, itself among the most influential innovations in modern music history. On tracks like “F*** Tha Police”, “Straight Outta Compton”, and “Gangsta Gangsta”, the group imbibed the righteous anger of KRS-One and Rakim and Public Enemy, then spat it back out, dripping in bile. They told stories of the ignored, and forced a nation to listen.

Twelve months later, Cube had quit following a fallout over royalties, and begun taking his first steps to household name status. In the years since, he’s maintained a platinum-plated solo career, notched regular box office hits as an actor and producer, and remained fiercely outspoken about the systemic injustices faced by Black Americans. Not that you’d pick any of this up from the insouciance in his voice as it travels down the line from LA today.

“I started doing hip-hop as a hobby, as a pastime, something to just be creative, you know? I never thought I was gonna make a quarter in music,” he says. “And then I got my big break with NWA and now, I’m still doing what I had fun doing when I was just a youngster.”

Despite his credentials, Cube doesn’t feel like an elder statesman of the scene. He still has his idols. “I grew up adoring Run-DMC, they was to me the biggest and the best rap group of all times,” he says, a touch of childlike excitement creeping into his voice. This August, he’ll join them – along with Snoop Dogg, Lil Wayne and others – for a showcase marking hip-hop’s 50th anniversary at New York’s Yankee Stadium. The geographic location is deliberate – The Bronx is acknowledged as the genre’s birthplace – but the Google Pixel sponsorship and 46,000-capacity venue are two clear signs of how far the sound has grown since DJ Kool Herc started slotting together funk breaks at block parties in the Eighties. “To be able to share a stage with them, is [a kind of] pinch-yourself moment. Even at this time in my career, I still get a kick out of rubbing elbows with some of the greats.”

Along with contemporaries like Tupac or Snoop Dogg, Cube fits the mould of a pop culture icon: the sort of person that others pour their ambitions, intrigue, and animosity onto in equal measure. He’s a perplexing character who makes the methodical seem coincidental. But his creative drive is undeniable – and it’s been the binding agent in a miscellaneous career that’s spanned music, movies, and entrepreneurship.

I look at music, and my past music, as time capsules. I don’t want to erase the past just because I don’t like something I did

The 1991, Oscar-nominated film Boyz n the Hood was based on a song Cube wrote for NWA bandmate Eazy-E, and became his big screen debut, too. Since then, he’s been a consistent earner at the box office, starring in dial-shifting cult classics including the Friday franchise and Three Kings, along with family comedies like Are We There Yet?, where his gruff exterior provides a fatherly comic foil. A few days before this summer’s Yankee Stadium show, he’ll voice Superfly, the villain in Seth Rogen’s new take on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. (Cube admits he’s probably better known for his acting than rapping these days.) In recent years, he’s trained his creative eye on sports, too, launching a 3×3 basketball league, called BIG3, which is set to debut in London this summer. Ask him about any of these things and you’re met with an enthusiasm that belies the mean-mugging, curled-lip character that stares out from the cover of Straight Outta Compton, or AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, or War & Peace, or, for that matter, his lengthy Wikipedia page.

He’s less excited, however, by the prospect of another election cycle. The energy audibly drains from his voice at the mention of the upcoming 2024 contest. That jaded snarl comes out. “I think people are exhausted by all this bipolarism,” he says, referring to the United States’ two-party system. “But it’s the system that they’re stuck with, so what do you do?” He drew flack for taking meetings with Donald Trump’s campaign in 2020, and this week – after we talk – made a bizarre, possibly naïve, appearance on right-wing shock jock Tucker Carlson’s Twitter show to discuss his personal stance on Covid vaccines. His politics are hard to pin down, but he feels like he’s been saying the same thing for three decades; he’s fought persistently for better rights for Black Americans. Despite insisting he has no truck with politicians (“They just tell you what you want to hear to get your vote, and then pretty much go off and do what the hell they want to do once they get it”), he’s made trade-offs for proximity to power. Mostly, he’d rather spend his time doing things than explaining them: his go-to filler phrase is “you know”.

As the main rapper and ghostwriter for NWA, Cube was responsible for the group’s strident and provocative political tone – sparking moral panics about what was then a burgeoning, hardcore strain of rap, while drawing attention to police brutality and systemic inequality. He sees instances of modern rappers like Young Thug having their lyrics used as evidence against them in criminal trials as just the latest example of state antagonism.

“The powers-that-be really hate hip-hop in a lot of ways, and they’ve been looking for ways to destroy the spirit of hip-hop, to make people fearful,” he says. “It’s ridiculous to take music or lyrics into court. A lot of rappers don’t even write their own lyrics. So, to pull those up in a case, it would be like me trying to arrest Keanu Reeves and saying, ‘You sparked violence with John Wick, you shot a lot of people in that movie and somebody got shot around the corner and it might be you.’ At some point it becomes absurd to take art and treat it as evidence. And it’s only happening, from my understanding, in hip-hop.”

Does he still believe in the power of music to shift the agenda? “I don’t know if someone’s in the [voting] booth thinking about their favourite rapper before they pull the lever,” he says. “I think music and art can bring up things that you may not have been thinking about, and can make you more informed. It can make you go seek the information for yourself. I think that’s what the power of music and art does – it’s just opening your mind to different concepts, to different ways of thinking than probably your circle and the people around you.”

He’s not sure he hears much of that in modern rap, though. “In the early Nineties, hip-hop was still somewhat of a pure form,” he says. An inevitable “but” hangs in the air. “But after that, after companies like [the multitrillion-dollar asset management firms] BlackRock and Vanguard started controlling the music industry, then of course the agenda changed. They pushed that kind of music out and popularised the music that ain’t really talking about nothing but sex and cars and girls and clubbing and jewellery and bulls***. They pushed that to the front and made that the most popular rap. And they have the power to do that, because they control the radio stations, the television networks, they control most of the outlets.”

‘This s*** about to pop’: Cube and Dr Dre at the 2000 Source Awards

‘This s*** about to pop’: Cube and Dr Dre at the 2000 Source Awards (Getty Images)

This is, Cube suggests, because BlackRock and Vanguard have investments in private prisons, and therefore stand to profit from popularising the types of behaviour that land more people in those private prisons. “[They] don’t want to do nothing that’s going to liberate you,” Cube continues. “They want to push music that has no substance, so the people listening won’t have no substance.”

It’s a confusing logic, though one that’s popular in purist hip-hop circles – and, like all the most pernicious conspiracy theories, rests on a grain of truth in its critique of the reductive nature of capital. (BlackRock and Vanguard do manage investments in both the music industry and private prisons).

Extrapolating this kind of conspiracy theory from discrete facts has landed Cube in trouble before. In 2020, The Daily Beast reported on his history of engaging with antisemitic conspiracy theories, after he shared a series of dog-whistling memes with the more than five million followers he’s amassed on Twitter. The report also mentioned Cube’s 1991 album, Death Certificate, which was issued in a shortened version in the UK for fear that laws against racial incitement would see it banned entirely. One song in particular, “No Vaseline” – a diss track aimed at Eazy-E and the group’s Jewish manager Jerry Heller – was singled out for its lyrics accusing Eazy-E of letting “a Jew break up my crew”.

Last October, Cube felt compelled to refute Kanye West’s claims, made during an appearance on a since-deleted episode of the Drink Champs podcast, that Cube had “really influenced” him to “get on this antisemite vibe”. That same month, West was kicked off social media after embarking on a posting spree that included threats to go “death con 3 On JEWISH PEOPLE”. West later attempted to walk back his comments, saying he “likes Jewish people again” after watching Jonah Hill in 21 Jump Street (a comedy film that, coincidentally, co-starred Cube).

“I don’t know what [Kanye] meant by it, he’ll have to tell you,” Cube says of the incident now. “I just didn’t want to be misconstrued that I was telling him to spread the message. It’s not true. Matter of fact, I was telling him just the opposite.” He’s previously expressed regret at referring to Heller directly as a Jew in “No Vaseline”, but remains forthright about the issues he had with him over royalties and contracts. “When it comes to Jerry Heller, it’s the truth. Where was I incorrect?”

In recent years, “No Vaseline” has re-entered Cube’s live setlist – though generally cutting off before the lyrics that target Heller. It’s not uncommon for rappers to play excerpts of songs when they’re cycling through extensive discographies in a 90-minute set; Cube has 10 solo albums plus multiple collaborative efforts to his name. But Cube’s reasoning in this case is more than just a practical decision: “No Vaseline” is still held up by many as one of the greatest diss tracks of all time.

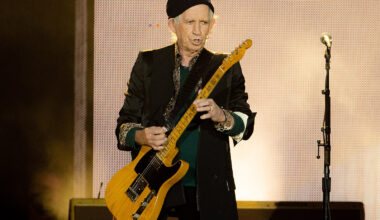

‘The glory of life is why I get out of bed’: Cube in concert this month

“I look at music, and my past music, as time capsules,” he says. “I wouldn’t go back to change anything, because it reflected to me the thought process at the time … I don’t want to erase the past just because I don’t like something I did. To me, it’s an opportunity to not only do the song, but to now say what you think about it and how you reflect on the song after it’s done. It gives you a chance to explain to the audience your feelings and the things you felt about the song back then, why you did it back then, [and] why you don’t think now it’s appropriate. But if you just don’t do it and pretend that it never existed, people are going to listen to it anyway. Why not listen to it with your new explanation on what you think of it?”

It’s a revealing attitude – and one that, in many ways, scythes through the more bone-headed debates about free speech and so-called “cancel culture” that Cube has otherwise courted. But this is also a man who’s never shied away from the apparent contradictions in his character. If anything, he’s mostly sought bigger stages to reflect them on: the gangster rapper embarking on family comedy franchises, the independent thinker who invites the scrutiny of interviews. He wheels out wild conspiracy theories just as freely as marriage advice (“respect,” he says, and being “willing to learn from each other” are the cornerstones of his 33 years and counting). He’s at once the 50-plus father of four and the teenager weighing the balance between studying and provocative hit singles – and choosing to do both. And in August, he’ll be the scene veteran giddy to share a stage with his pioneering heroes.

“The glory of life is why I get out of bed,” he says. There’s that childlike excitement again. “I feel blessed to be in a position that I always dreamed of. I love to do cool stuff, I love to create. And that’s what we’re here to do: we’re here to create cool stuff.” But even while marking a half-century of a culture his creativity has been so integral to, Cube is focused on what’s next. “It’s not about what I’ve done, it’s about what I’m about to do.”