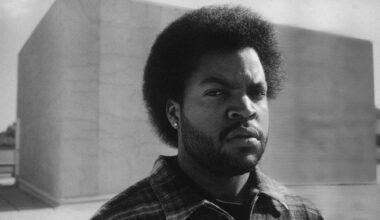

The Detroit rapper’s case puts the Music Modernization Act under threat

On August 21, Eminem music publisher Eight Mile Style slapped Spotify with a massive copyright infringement lawsuit. Filed in Nashville federal court, the complaint claims that Spotify streamed the rapper’s songs billions of times without the necessary license, accounting, or payment. But whether Spotify properly paid for the use of more than 200 Eminem songs may not even be the most significant point of contention. The suit also claims that the Music Modernization Act, a law unanimously passed by both chambers of Congress last year with wide support across the music industry, violates the U.S. Constitution by restricting these types of cases.

Eminem himself isn’t directly involved in the suit, only the Eight Mile publishing company, which co-owns the songs and handles their copyrights. And the litigation focuses on just the “compositions”—essentially, the lyrics and sheet music—not the “master recordings” at issue in another prominent copyright dispute right now, Taylor Swift’s feud with her former label Big Machine. But this case clearly isn’t your garden-variety copyright infringement lawsuit. In fact, like in “Lose Yourself,” one of the many Eminem hits affected, Eight Mile’s legal contest with Spotify may represent something of a big moment for the music industry. The lawsuit was filed by Richard Busch, the same attorney who won the influential “Blurred Lines” copyright verdict.

Start with Eight Mile’s claim that Spotify had no license for the affected Eminem songs. According to the complaint, the songs were categorized by Spotify under “Copyright Control,” meaning who owned the copyright was unknown—a designation that the lawsuit asserts was “absurd,” considering it involves “one of the most well-known songs in history.” The complaint also cites alleged irregularities in the payments for the plays of “Lose Yourself,” “Stan,” “Without Me,” “The Real Slim Shady” and other big hits, claiming that Spotify sent “random payments of some sort, which only purport to account for a fraction of those streams.”

“A lot of companies who don’t really go to great lengths to find out whom to pay oftentimes put stuff into [copyright] control and wait for somebody to come and claim it,” says music lawyer Owen Sloane. “In a case like [Eminem’s], where you would have a modicum of effort to find out who it was, it seems a relatively lame excuse.”

Sloane notes that the complaint also brings up a bigger issue about how streaming companies do their accounting for enormous numbers of streams, each generating a fraction of a penny in payment. “You’re being paid such small amounts for each stream that the statements are really almost un-auditable, because there’s millions of entries, especially on a song that’s streamed constantly,” he says.

Sloane says the copyright claim will likely be settled rather than go to trial. “It’ll probably be a battle of expert accountants.” John Krieger, another lawyer who has represented musicians on intellectual property matters, shares a similar view. “If it can happen to Eminem, it can happen to a smaller artist,” Krieger tells me. “Assuming that the allegations in the complaint are true, Eminem’s company has a fairly good chance of prevailing or of probably getting Spotify to some kind of settlement.” Spotify hasn’t responded to Pitchfork’s requests for comment on the lawsuit.

But if a cash settlement is a simple prospect, Eight Mile’s constitutional claim about the Music Modernization Act could perhaps ultimately be a question for the Supreme Court.

The first major overhaul of music’s copyright law in two decades, the MMA is complex and far-reaching, but it’s essentially supposed to streamline music licensing and royalty payouts for the streaming era. The product of years of compromises, the law was the rare proposal endorsed by lawmakers from both parties and groups representing nearly all sides of the music industry. Republicans and Democrats, songwriters and Spotify, indie labels and Donald Trump: All saw a bill they could get behind.

Still, the MMA has not been without critics. An early voice calling out flaws in a predecessor to the final bill belonged to Busch, the attorney representing Eight Mile in this case. As a carrot to bring streaming companies on board, the legislation shields Spotify and its rivals from expensive copyright claims. Not coincidentally, one music publisher filed an infringement lawsuit against Spotify as the bill was looming. As far back as February 2018, Busch was arguing that this element of the MMA was unconstitutional. “It also strikes me as odd why we would be so concerned with basically forgiving Spotify from real liability for years of allegedly willful infringement (while they built a multibillion-dollar business with no assets other than songs) just because a lawsuit has not yet been filed,” he wrote in a Tennessean op-ed.

Specifically, the MMA makes it harder to sue digital music services for “statutory damages.” Awarded at a judge’s discretion, these are amounts based on the law rather than calculated based on how much money the people suing might actually have lost because their songs were being streamed. Statutory damages can be as much as $150,000 per infringement—which, in cases like Eight Mile’s, adds up pretty quickly.

The Eight Mile lawsuit brings Busch’s statutory-damages argument out of the opinion pages and into the courts. The complaint alleges the law violates the Fifth Amendment—namely, the Due Process Clause and the Takings Clause, which respectively guarantee a right to fair treatment through the court system and forbid seizing private property for public use without permission. Although Harvard Law School Professor Laurence Tribe tells me that Busch’s argument here is “very substantial,” the U.S. Copyright Office declined to comment about the case, citing the pending litigation; the U.S. Department of Justice didn’t reply prior to deadline.

The lawsuit also raises a separate question about statutory damages: Are they appropriate in the first place? As recently as 2013, the Supreme Court declined to strike down a jury’s verdict that an individual music downloader should pay the recording industry statutory damages of $220,000 for sharing merely two dozen songs over the defunct file-sharing service Kazaa. “The U.S. is unusual in its application of statutory damages,” says Jim Griffin, managing director of digital music consultancy OneHouse and a former Geffen Records tech executive. “Generally, the copyright law in other countries seeks to make plaintiffs whole for the royalties they should’ve been paid. As they should be.” Under U.S. law, plaintiffs can be reimbursed plus demand tens of thousands of dollars per infringement.

Overall, as lucrative and contentious as statutory damages can be, they’re only one piece of the MMA, a 66-page law that dealt with a range of industry concerns. “The process of getting legislation passed necessarily involves give-and-take and compromise, and it’s unsurprising when some stakeholders aren’t entirely happy with the compromise that’s ultimately struck,” says Kevin Erickson, director of the artist-advocacy nonprofit Future of Music Coalition. “The success of the new system will be dependent upon building in as much transparency, openness, and accountability from all parties as possible.” The Eminem publisher’s legal fight with Spotify is an early test of that spirit.